Acid Mine

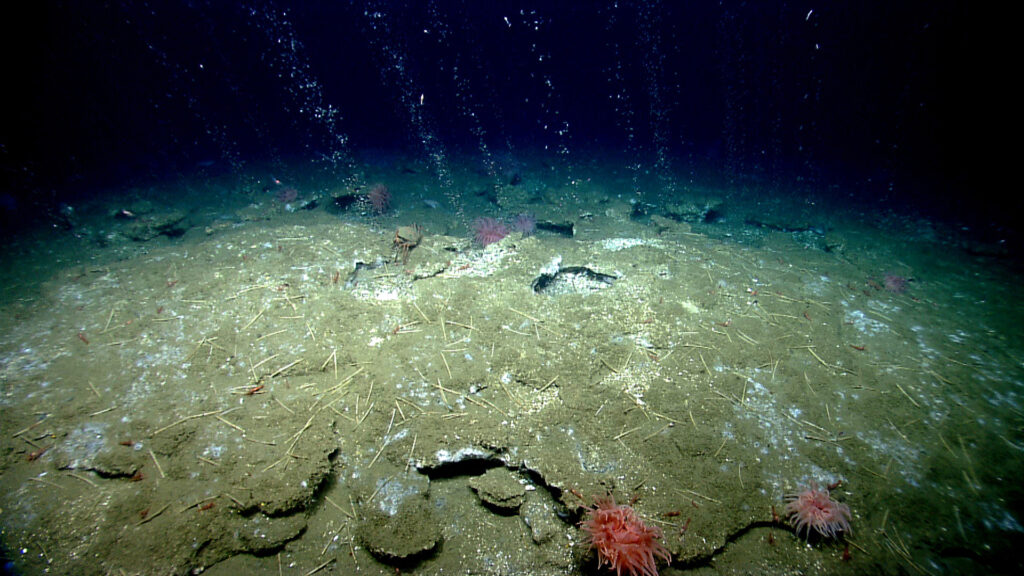

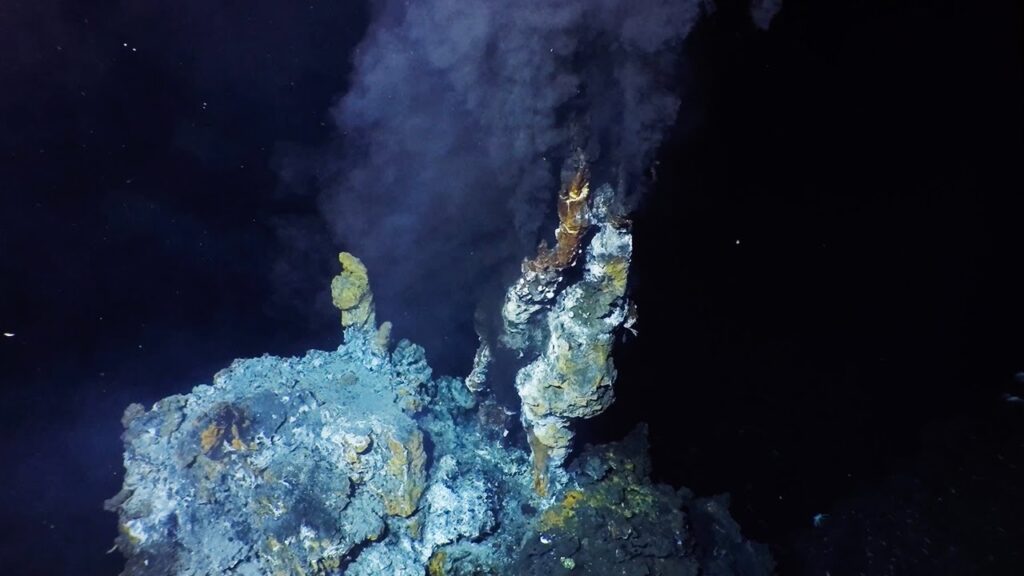

Acid mine environments arise where mining exposes sulfide minerals, which then oxidize and produce acidic, metal-rich waters. pH values can drop below 3, and concentrations of iron, copper, and other metals are often high enough to be toxic to most organisms. Extremophilic microbes that inhabit these sites tolerate both acidity and metal stress, and can take part in further mineral weathering and metal cycling.